So I've been a little busy this month...

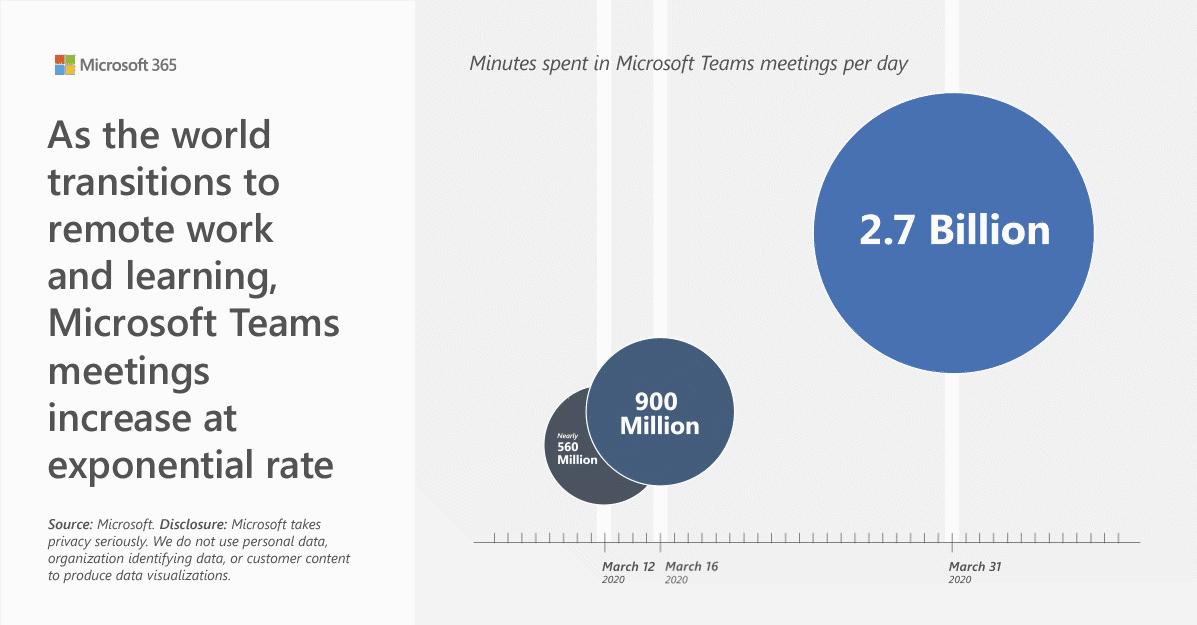

To see the full report Microsoft produced on the ways COVID-19 have changed the way work is done, see https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/blog/2020/04/09/remote-work-trend-report-meetings/.

For just a summary of the numbers, hit up https://venturebeat.com/2020/04/09/microsoft-teams-breaks-daily-record-with-2-7-billion-meeting-minutes-tops-mid-march-high-by-200/.

For a detailed engineering look into some of the ways Teams is using AI to make remote meetings better, take a look at https://venturebeat.com/2020/04/09/microsoft-teams-ai-machine-learning-real-time-noise-suppression-typing/.

Oh my goodness, this is insane. I want one.

Marriage ends up as a hopeful, generous, infinitely kind gamble taken by two people who don't know yet who they are or who the other might be, binding themselves to a future they cannot conceive of and have carefully avoided investigating.

— Alain de Botton, Why You Will Marry the Wrong Person

The Spycraft Revolution →

The world of espionage is facing tremendous technological, political, legal, social, and commercial changes. The winners will be those who break the old rules of the spy game and work out new ones. They will need to be nimble and collaborative and — paradoxically — to shed much of the secrecy that has cloaked their trade since its inception.

The biggest lie tech people tell themselves — and the rest of us →

Technologists' desire to make a parallel to evolution is flawed at its very foundation. Evolution is driven by random mutation — mistakes, not plans. […] Evolution doesn't have meetings about the market, the environment, the customer base. Evolution doesn't patent things or do focus groups. Evolution doesn't spend millions of dollars lobbying Congress to ensure that its plans go unfettered.

Not all technology is neutral and it's worth considering the ramifications of our choices rather than arguing that progress is the natural state of things. All these decisions are made with an intent, but they should be with intentionality.

The Supermarket

I went to the supermarket today so you don't have to. In liu of live-tweeting societal breakdown, here are some hopefully amusing vignettes.

Cleaning wipes were available upon entering the store. They have not yet been stolen unlike the whole hand sanitizer dispenser stand at the Safeway down the street. I think they were actually moist dryer sheets, but the hospitality was still appreciated.

All the bottled water was gone. No, bottled water is not needed.

Everyone keeps asking me if I have enough toilet paper. I respond "How much is enough toilet paper?" Everyone laughs. No one answers. I may never ever know.

The groceries I buy regularly have a suspicious overlap with the list of recommended emergency non-perishables. It's unclear if my diet is just constantly in a state of emergency.

There is only one worthwhile brownie mix, Ghirardelli triple chocolate:

Chicken? Running low. Breaded pre-cut frozen chicken in cute dinosaur shapes? Running right into my tummy.

What does it say about us when the only soups left on the shelf are Campbell's chicken noodle and all the Campbell's Chunky™? What does it say about me that those are the only soups I buy?

There are debates in the world that will likely never end. Coke vs Pepsi. Waffles vs pancakes. T-Rex vs Velociraptor. Prego vs Ragu is now definitively over. Even the mushroom-flavored Prego was gone.

Oreos are not a panic buy. Not even the double-stuffed. I'm unclear why not.

I was surprised the store-brand thin crust pizzas I like were sold out until I remembered I was at a different brand store.

There's nothing like a disaster to make us re-evaluate our priorities and judge what's really important. Avocados.

People will risk leaving the safety of their homes to scavenge through a desert of groceries for milk and eggs in order to avoid just-add-water Bisquick pancakes.

"Did you find everything you were looking for today?"

My bank notified me of a suspicious transaction. I think it's because I spent money on groceries.

The Money Farmers: How Oligarchs and Populists Milk the E.U. for Millions →

Every year, the [E.U.] pays out $65 billion in farm subsidies intended to support farmers around the Continent and keep rural communities alive. But across Hungary and much of Central and Eastern Europe, the bulk goes to a connected and powerful few. The prime minister of the Czech Republic collected tens of millions of dollars in subsidies just last year. Subsidies have underwritten Mafia-style land grabs in Slovakia and Bulgaria.

Europe's farm program, a system that was instrumental in forming the European Union, is now being exploited by the same antidemocratic forces that threaten the bloc from within. This is because governments in Central and Eastern Europe, several led by populists, have wide latitude in how the subsidies, funded by taxpayers across Europe, are distributed — even as the entire system is shrouded in secrecy.

Christians and the Coronavirus: Prepare to Lose →

The duty of Christians is to prepare in advance so that when the moments of crisis come — when there are too few ventilators, or there is too little money, or there remain too few supplies — the disciple of Christ can see the cost that someone has to bear and choose whether or not to bear that cost, or at least share in it.

[T]he reminder that the Christian faith carries with it not simply an acknowledgment of the inevitability of death but also the promise of a bodily resurrection [is] all the more astounding and all the more seemingly out of step with an era in which our bodies are sacrosanct and in which sickness is seen as such an alien part of the human condition.

— Tara Isabella Burton, "Fleeing coronavirus and finding our mortality"

There is grace to be found in learning how anxious and afraid we actually are. It is a grace to learn how much of a jerk we can be to our neighbors when we fight over toilet paper and hand sanitizer. It is a grace for those that have been overreactive and also for those who have brushed it all off as not-serious. The worst being brought out of each of us can be exactly what reveals our need for Jesus — the one person who really does save us from ourselves.

— Bryant Trinh, "The Pandemic and the Coffee Shop"